- Home

- J. S. Puller

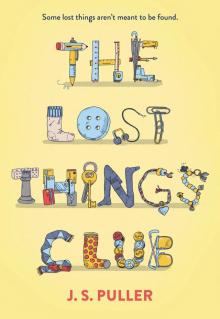

The Lost Things Club Page 3

The Lost Things Club Read online

Page 3

“With a lawn chair?”

“Well, what else am I supposed to sit on? The ground? That’s a one-way ticket to the ER for sure. Have you seen the way Chicago people drive?”

I shrugged. “Do you have to sit out here? Couldn’t you just leave a sign or something that says dibs?”

She chuckled. “A sign? That’s adorable. No one pays attention to signs,” she said. “You have to enforce dibs, otherwise, you lose it. My uncle Al guards his spot with a baseball bat, but my mother won’t let me. Going on and on about it being illegal or something.” She raised both eyebrows, shaking her head.

“Oh.”

“So what school do you go to?”

I had no idea where the question came from, and it took me a second to remember anything about myself at all. “Uh, Kohn Junior High.”

“Never heard of it.”

“It’s in Deerwood Park.”

“Oh. The suburbs.” She said it as if, somehow, that explained everything about me. And maybe it did. “You must be TJ’s cousin.”

I blinked in surprise. “Yeah. How’d you know?”

“I saw you arrive yesterday.” Her gaze darkened for a moment. “The lady driving your car tried to take this spot. But my father called dibs. I set her straight about that.”

Now that I thought about it, I vaguely remembered my mom almost pulling into a spot. But I’d been on my phone and hadn’t seen this strange girl sitting there.

My mom wasn’t easily intimidated.

But this girl just might be the exception to the rule.

I held up my hands in a gesture of surrender. I didn’t really care where my mom parked. The girl seemed to accept that, because the darkness lifted and she gave me a smile. That felt like an invitation, so I came closer. She smelled of sunscreen and something else, something sweet. Like one of those bear-shaped bottles of honey they kept in the kitchen at my mom’s office.

“You know TJ?” I asked.

“Sure,” she said. “I live right across the street from your aunt and uncle.” She pointed to a town house on the opposite side of the street, with a redbrick facade and a crooked iron gate. “And TJ and I go to the same school.”

“Chancelor?”

“Yeah. I see him sometimes in the hallways. He was in Mr. Hiler’s class. Ms. Berns the year before that. I had both of them when I was a kid. He’s reading buddies with my best friend, Samantha. Or, he was, anyway. And I’m pretty sure he was in gardening club last year. I was only a regular member then, but now I’m a vice president and I’m hoping to be president next year.”

President? Somehow, I got the impression that she would make a very powerful and iron-fisted dictator.

“What grade are you in?” I asked her.

“Going to be in seventh grade when school starts up again.”

Like me.

“Why aren’t you in middle school?”

“We don’t have middle schools in Chicago,” she replied. “Our schools go all the way through eighth grade. Then we get to apply to high school. I’m already trying to decide which high school I want to go to. I mean, the selective enrollment schools are great, but personally, I think I’d rather go to an IB school. A couple of schools around here offer an International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme. They’re really competitive. Colleges like them. And I appreciate the service element that goes into the diploma. My favorite program is definitely—”

“Do you like it?” I asked. “Not having a middle school? Being stuck in the elementary school with the little kids?”

She shrugged. “It’s fine, I guess.” She hooked her pen into the spiral of her notebook and then reached up above her head with her long, spindly arms, stretching out to her fullest length.

“My name’s Violet,” she told me. “Violet Kowalski.” She held out her hand. It was a very, very formal posture. I’d sometimes practiced handshakes with my mom, when she introduced me to the people she worked with at the university, but never with someone my age before. But Violet’s hand just hung there, waiting for me.

Oh, this was awkward.

“You shake hands?” I asked.

“Of course. It’s excellent practice for job interviews.”

“What?”

“Jooooooooooob interviiiiiiiiiiieeeeeeews,” Violet said, drawing out the words.

“You go on job interviews?”

“Well, not yet. But I will, someday. I mean, I plan to have a job. And you have to be prepared for the future. The handshake is everything. Too limp and no one takes you seriously. Too firm and people think that you’re trying to prove something, which, of course, you are, but you can’t let them know that.”

“Oh.”

What could I do?

I shook her hand.

Her fingers were like steel, the bony knobs of her knuckles digging into my skin.

“My name’s Leah Abramowitz,” I said.

“Leia? Like the princess from Star Wars?”

“No.” I groaned inwardly because I got that all the time. My dad actually did want to name me after the Star Wars character, but my grandmother insisted that he give me a traditional Jewish name. She also wanted him to follow custom and name me after a deceased relative—specifically my great-aunt Emily. They ended up compromising, and I became Leah Emily instead. “Leah.”

Violet nodded curtly. “Nice to meet you. Say it again.”

I blinked. “What?”

“Saaaaaaaaaay iiiiiiiiiiiiit agaaaaaaaaain. Your name. Let me hear it.”

“Leah Abramowitz?”

“Slower.”

“Leeeee—”

“Leeeee—”

“Uhhhh.”

“Leeeee-uhhhh. Leah Abramowitz,” she said. She spoke carefully, copying the sound of each syllable. “Is that right?”

“Yeah,” I said.

“Good. It’s important to get someone’s name right the first time. It proves that you’re listening and that you take an interest in what they have to say. And it earns you respect in formal environments.”

“Uh, thanks, I guess.” I was beginning to get the sense that Violet had a lot of rules buzzing around inside her head, like bees in a hive. “Do you sit out in this spot every day?”

“Mostly just in the summer,” she said. “I mean, I go to school when there’s school to go to.”

She sounded just like TJ. Or, well, how TJ usually sounded. He loved school. He would go on and on about his favorite lessons and friends and books.

He isn’t talking.

And I wasn’t exactly helping him, all the way out here. But maybe I had an opportunity staring me in the face.

I frowned a little, lowering my voice. “Hey,” I said to Violet, “were you in Chancelor the day that…”

“The shooting?” Violet asked.

“Yeah.”

She nodded. “But the sixth graders were in the middle-grades hall,” she said. “The shooting happened on the other end of the building, in the elementary wing.”

“Elementary wing?”

“Yeah.”

I felt fear rise up inside me and had to force it down my throat. No fear allowed. “Is that where TJ would have—”

“His classroom was there, yeah,” Violet said. “But if you’re asking if he was there, he wasn’t. He was in the principal’s office when it happened.”

“The principal’s office?”

“Priiiiiiinciiiiipaaaaaaaaaal’s offfffffiiiiiiiiice. That’s what I said.”

“But why?”

Violet shrugged. “He got into trouble for fighting.”

Trouble? Fighting? “That doesn’t sound like TJ.”

“True,” Violet said. “I mean, I’ve known him his whole life, practically. He’s such a sweet kid. Really. But it’s a lucky thing he was there. I mean, it was probably the safest part of the building.”

I smiled a little bit. “It’s not often that you’re lucky to be in the principal’s office. Last time I went there, my mom grounded me for a week.”<

br />

“What did you do?”

“Checked my email during science class.”

Violet snorted.

“What was it like?” I asked. “The shooting.” I knew it was probably an inappropriate question, but I couldn’t really help myself. You didn’t get to hear the story firsthand often. It was always filtered through the news and the internet and people’s loud opinions. Violet, though, seemed… direct. And not at all filtered. If I could ask anyone—if I could get the straight facts from anyone—it would have to be her. “What was it like?”

“Scary, I guess,” she said. For the first time, there was a slight sense of softness in her voice. She’d slipped back into the memory of the day. I guess she was human after all. “I remember it was really quiet. And then, there was this announcement on the PA about how we had to shelter in place.”

“What does that mean?”

“Squat down against the wall with the lights out and the door locked. And just kind of wait.”

“For what?”

“For the police to tell us to leave the building.”

“That’s it?”

“That’s it.”

“That… doesn’t sound so bad,” I said.

“Well, not for us, it wasn’t.” Violet’s voice dropped to a hiss, and she leaned closer to me. “But you know, we lost a kid.”

“Lost?”

“He died. A few hours after they rushed him to the hospital.”

My eyes widened. “I didn’t know that.” And I should have, too. Why hadn’t I searched for the shooting online?

Violet nodded. “I didn’t know him personally—his family had just moved into the neighborhood—but we heard about it. We all heard about it. There was a candlelight vigil down the street. Almost every family in the school was there, and Star Williamson’s father brought cookies with peanut butter in them. And Camilla Goelz’s mother asked what he was thinking, was he trying to kill everyone?” She shook her head. “It was a whole ordeal.”

“Was it hard to go back to school?” I asked.

“Yeah, a little bit,” Violet said. “We all had to go in groups to talk to the counselor and everything. And all the teachers kept promising us over and over again that the school was safe and that the world is a good place and that there are just sometimes people in it who do bad things.”

Counselors. Just like Uncle Toby said. It didn’t make a lot of sense, though. Violet seemed, well, she wasn’t exactly normal. But she was talking. She was out. She seemed just fine.

So why wasn’t TJ?

It just didn’t add up.

There was a low roll of thunder from somewhere in the distance. “Oh,” Violet said, sitting up a little in her lawn chair. “I hate it when the weather forecast lies. There was only supposed to be a five percent chance of rain today. I don’t have time for this noise.”

I shrugged. “Sorry?” I said. I didn’t know why I felt the need to apologize. It wasn’t my fault that Violet was disappointed in the weather.

“How’s TJ doing, anyway?” She asked it so suddenly that it nearly gave me whiplash.

“What?” I said.

“TJ. Your cousin. Remember? How’s he doing? I know it hasn’t been easy for him. He never comes out to play in the water.” She gestured to the kids with the inflatable pool. “And he did that all the time, last summer. I was holding dibs then, too.”

“He’s… uh.” What could I say? “I don’t know. He’s… well. He’s really, really quiet.”

He isn’t talking.

But I couldn’t bring myself to say it.

“So, not so great?”

“No.”

She nodded. “Is he still sneaking out?”

“Is he still what?”

In my head, I heard the sound of a needle scratching a record. A sound effect the internet loved to pair with shocking information.

Violet couldn’t be serious.

Sneaking out?

“Sneeeeeeakiiiiing”—she spoke slowly and loudly—“oooooout.”

“What are you talking about?” I asked.

“I’ve seen him,” she said. “Sometimes at night. Usually after dinnertime. He comes out.” She pointed to the front door of the apartment building. “And heads off that way.” Her fingers walked the sidewalk, down to the far end of the block.

“Where does he go?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” Violet said. “I just know it’s sneaky.”

“How do you know?”

“Well, he’s not allowed outside after dinner by himself.”

“How do you know that?”

“I make it my business to know what’s happening in the neighborhood,” she said smugly. Leaning over in her chair, she pointed to the girl bouncing the soccer ball off her head. “Daisy Jackson isn’t allowed to date until she’s sixteen, so she has to meet her boyfriend at the corner any time they want to go out together.” She pointed at one of the little kids in the pool, a girl with an enormous head of black curls, slipping and sliding on the grass. “Deanna Merchant is allergic to peanuts and strawberries, so she’s not allowed to eat dinner at anyone’s house.” She pointed to another kid, this one a thin, blond boy with hair like the head of a dandelion. “Perry Michaelson got after-school detention three days in a row when he told Ms. Lipski that she was stupid.” She turned back to me. “And those are TJ’s mother’s rules. No going outside alone after dinner.”

“Oh.” I frowned, brushing one of my fake curls back, behind my ear. “That’s… I don’t know what that is,” I admitted. “It’s weird. Him sneaking out. So weird.”

Violet looked up at me. There was a hunger in her eyes. She wanted to know what I knew. “Isn’t it?”

Well, it wasn’t TJ. I knew that. My little cousin didn’t go out by himself. Except for the fact that he apparently did.

So what was my responsibility here?

Was it my job to tell Uncle Toby and Aunt Lisa?

Probably.

But how could I tell them when I didn’t know what there was to tell?

You couldn’t share a story until you knew it.

So that’s what I would do.

Learn the story.

If nothing else, I was sure that it was the key to helping TJ.

CHAPTER THREE

I hid my phone under the table.

Aunt Lisa didn’t allow cell phones during dinner, but I was on a quest and I couldn’t stop now.

I searched for “sneaking out.” Not surprisingly, I didn’t find an answer right away. Instead, I pulled up a bunch of articles in teen magazines, offering tips on the best ways to sneak out without getting caught. Apparently, TJ had already mastered that part. I scrolled down, down, down, until I stumbled on a list of popular movies about sneaking out.

I knew it had nothing to do with TJ, but I was curious, so I clicked on it.

Ten clicks later and I realized that I was reading about the history of Pixar.

So I went back to the start. New search terms: “why do kids sneak out?”

The problem was that Aunt Lisa was eyeing me like a hawk, so it was hard to read more than a few sentences at a time. She seemed to be taking some kind of weird pleasure in watching me eat. I could only search in little, stolen moments—when she got up to find the pepper or refill her glass of water or open the window.

Dinner was catfish, buttery squash, and a sugar-free pecan pie for dessert.

“I haven’t made most of these dishes in years,” Aunt Lisa said, resting her chin in her palm. “We’ve turned into a real take-out family. Glad to know I haven’t completely lost my touch.” Her stare was a little creepy, but I kind of got why she was watching me. I didn’t see TJ take a single bite. He cut his food up into tiny pieces and pushed those pieces around on the plate, so it looked like a rodent had been nibbling away at his dinner. And no matter how much Aunt Lisa tried to get him to eat, he just sat there stubbornly, his eyes never really focusing on any one thing.

Until there was a lou

d boom from the street.

I guess it was a car backfiring. A sound that was half like a firecracker and half like a door slamming shut. I heard it so often in Deerwood Park that I’d sort of forgotten it was a thing. We just ignored it and life went on.

But TJ heard it.

He let out a sound—the first I’d heard him make. It was like some kind of animal. A wail that came from a place deep inside. His face wrinkled in terror. He curled in on himself and fell under the ledge of the table. Aunt Lisa let out a gasp, and Uncle Toby immediately hopped out of his seat, knocking over the bottle of orange pop he’d been hiding behind his chair leg. I leaned over to one side to get a better look, slipping my phone under my napkin. Uncle Toby pulled TJ up against his chest, hugging him tightly.

“It’s all right,” he said, stroking TJ’s hair. “It’s all right, kiddo. Just a car. Nothing to worry about.”

“You’re safe,” Aunt Lisa said, leaning over the two of them, putting her hand on top of TJ’s head. “Totally and completely safe. With your parents and your cousin who love you very much.”

The fear on TJ’s face dissolved as quickly as it came. But there was no relief after. He didn’t take comfort in the way that Uncle Toby held him. And none of Aunt Lisa’s whispering seemed to reach him. His face was like glass. Immovable.

The three of them sat like that for a good, long while—pop puddling on the floor beside them—before TJ turned to face his mom.

Aunt Lisa sighed. “It’s all right,” she said. “You can go to your room if you want, sweetie.”

TJ stood up, robotically turning from the table and walking down the hall, disappearing into his room as the swollen floorboards creaked under his feet.

With a swish, the door closed behind him.

Uncle Toby sat on his knees, grabbing a napkin to absently mop up the pop on the floor. And the three of us just fell silent. I tried to pick at my food a little. But that felt like pretending. I couldn’t pretend that whole thing hadn’t happened.

Could I?

I started to ask. “What just—”

“Finish your veggies, Leah.” Aunt Lisa cut me off sharply.

I finished my veggies.

The cabinet behind the table was calling to me. After dinner, as Uncle Toby sat on the couch, watching—but not really watching—a Cubs game, I heard the cabinet whisper. It was promising me answers. Stone-cold facts. I wondered if I could sneak over and find Aunt Lisa’s binder, look through it for some kind of explanation of what had happened at the table. Without getting caught. I got all the way to the cabinet and even got the door open, but then I heard the sticky smacking of Aunt Lisa’s bare feet approaching the living room. In a panic, I grabbed the first thing I saw, which happened to be TJ’s old one-hundred-piece jigsaw puzzle of an ice cream sundae, oozing with hot fudge and strawberry sauce.

The Lost Things Club

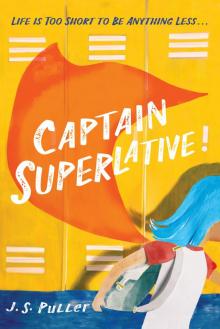

The Lost Things Club Captain Superlative

Captain Superlative